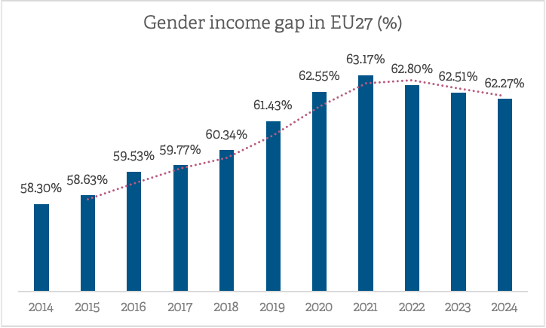

The ILO has estimated that the gender income gap – which is the ratio of women’s to men’s labour income – is 62,3% in 2024 and has only changed minimally over the last decade.

Source: Own elaboration based on ILO modelled estimates, March 2025

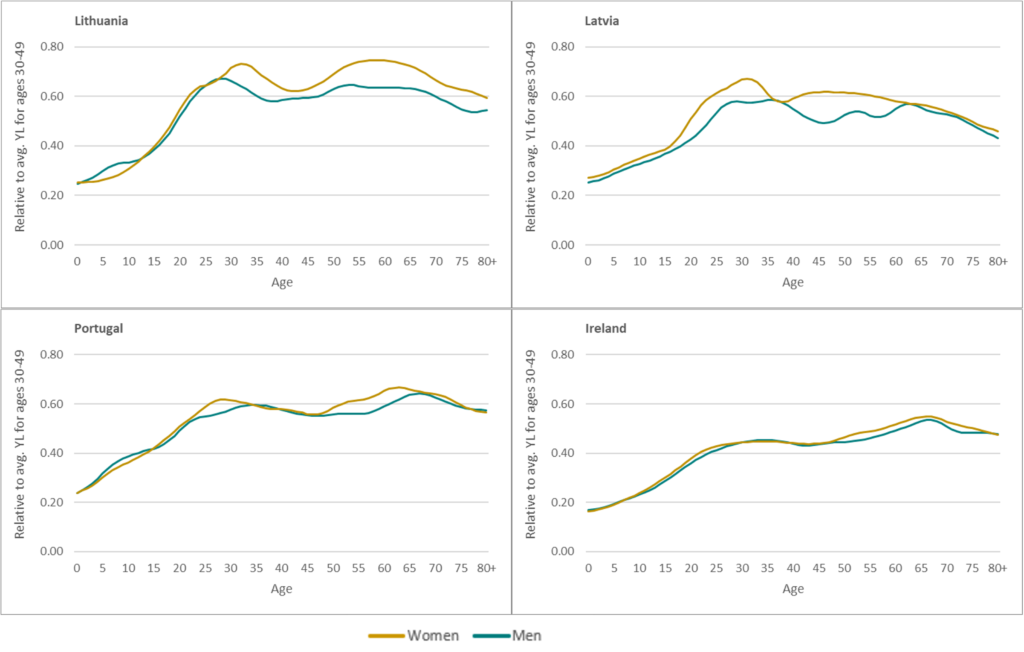

Within SUSTAINWELL, we take a wider perspective of the gender gap in a lifecycle perspective using the age profiles estimated by the National Transfer Accounts (NTA), including non-market production (National Time Transfer Accounts, NTTA). This allows us to build a foundation for designing evidence-informed solutions for policy development towards equal opportunities for all.

With our NTA estimates we find that there are considerable differences in labour income across the EU27 countries. In Greece, for example, the gender gap is relatively large, while in Slovenia and Lithuania it is among the lowest. Interestingly, in several countries the gender gap practically disappears at older ages, probably because of more equalised retirement ages for both genders.

We observe that gender gap in labour income is minor in Scandinavian countries and some post-socialist societies, whereas relatively bigger in some central and southern countries (where the traditional role of the family is still encouraged).

Yet, men earn more than women, private consumption seems to be higher for women than for men in most countries.

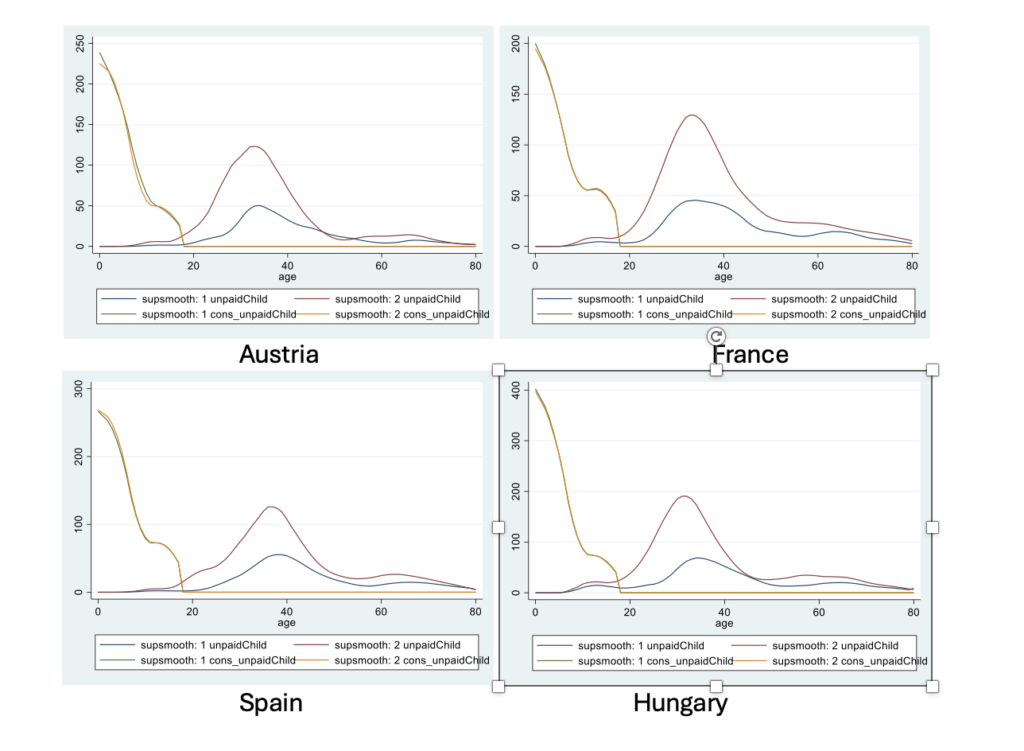

Childcare

When women and men start a family and receive pretty much the same childcare, we find that women produce much more in terms of childcare than men do, carrying out most childcare responsibilities. This gap persists in times of individuals being grandparents. Interestingly, smaller gender differences, however, can be observed in the home-produced childcare in Spain as compared with Austria and France, for example.

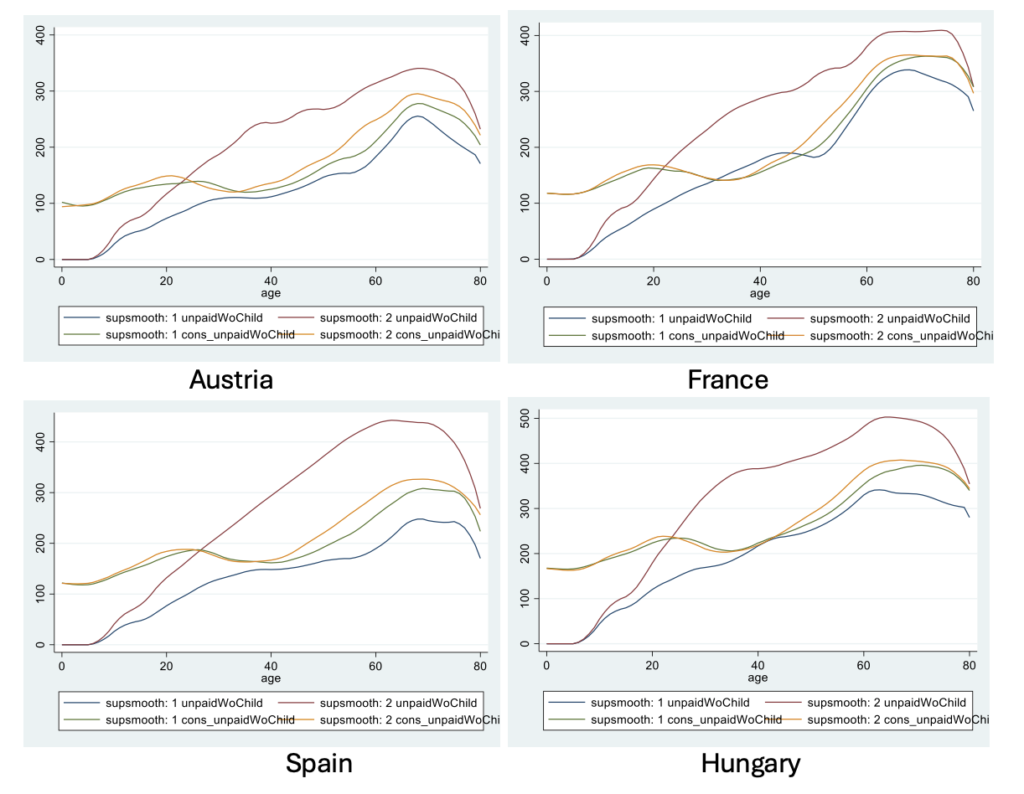

Unpaid work other than Childcare

Gender gap is also significant when observing the time devoted on unpaid work other than childcare which can include taking care of older adults, sick or disabled persons or household work and maintenance. This is particularly severe in the case of Spain where women spend considerably more hours in domestic and care work than men. This a key indicator of gender stereotypes and inequalities.

Whereas better work-life balance has become a key policy priority as being recognised by the EU Work-life balance Directive, the EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025 and the European Care Strategy where there is promise for affordable and high-quality support on early childhood education and care services and long-term care, there is still work to be done by national governments.

Source: Own elaboration by researchers Tanja Istenič and Jože Sambt (University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) and Bernhard Binder-Hammer (VID/ÖAW, Austria)

SDGs related to this research: