Sound installation

Sound installation is a multidisciplinary practice, based on concepts of space and sound. This theoretical and practical course is taught by a team of instructors composed of sculptors, musicians, an architects specialized in acoustics, and artists working in the field of transdisciplinary practice. The course will cover the fundamental concepts necessary to develop a practical project involving the syntax of three-dimensional space; spatial organization in urban spaces and natural environments; the organization of sound, project management in the acoustic space, and a critical investigation that interrelates historical aspects with the practical realization of a collaborative sound installation by the students.

This module is lectured by the professors Martí Ruíz, Pedro Alcalde, Mathias Klenner, Josep Manuel Berenguer and Ivonne Villamil with the following structure and contents:

Space – Marti Ruiz

This part of the topic will address the syntax of three-dimensional space and spatial organization in urban space and in the natural environment. Spatial structuring will be studied through narrative routes and space sequences and introduced into the materials, construction techniques and artistic processes required for understanding and practical experimentation in sound sculpture and installations in three-dimensional space.

- Geophonies of silence. Sound identity of the place, sound environments and active listening.

- Sound mapping and geolocation. Frontiers, levels and sound layers in urban space. Urban spaces defined by dynamics and mobility. Spatial and temporal trajectories. Sound compositions of urban spaces. Artistic mapping: maps of sounds, feelings and sensations. Graphical representation systems, reading codes, classification, processing and transmission of information. The city as text and stage, with multiple reading possibilities.

- Expose sounds. Experience sound with the timbre of materials and shapes. Cymatics, draw with sounds, images of how sound propagates into materials with geometric paths and patterns.

- Notions of space. Perception of space, physical, mental and sensory. Surfaces, territories and boundaries. Lines and routes in space. Trajectories, spatial and temporal stages. Rhythmic transitions and successions between spaces. Sound sequences, geometry of spaces and materials. Sound design of the space.

Sound – Pedro Alcalde

This part of the topic is interconnected with “Space” in shared sessions. Sound will be considered both, as itself and its relations with space.

- Sound, ligth, vision and other senses

- Texture maps

- Sound sources, attributes, morphologies, symbolism, aesthetics, ethics.

- REAL OR IMAGINARY SOUND MAP, mapping with audio files.

- Regulatory categories: linear / nonlinear, unit / multiplicity, durable / fleeting, objective / subjective, collective / individual, order / chaos, closed / open.

- Sound scenes

- Sound in interaction: installation, public spaces, urban planning, landscaping, architecture

- Theme, characters, action, space and time.

- Sound “in”, “out” and “off” – image / sound: identity, complementarity, opposition.

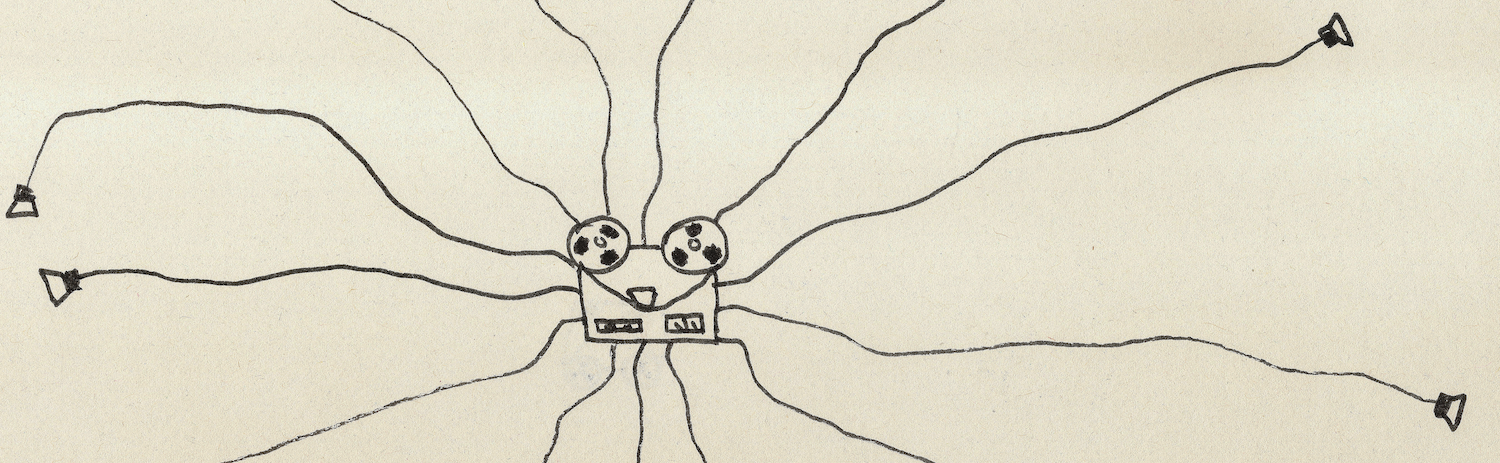

Project Management – Mathias Klenner

The Project is the set of activities performed by a person or entity to achieve a certain objective or outcome. These activities can be interprofessional and therefore very interrelated. The project is based on different knowledge that is displayed through diagrams, drawings, graphics, schematics, sketches, models and other kinds of representation, this information is presented in print and/or digital format, developed to determine in some type of support, such as a work or an installation. Since the objective pursued by the project must be fulfilled within a certain period defined above and respecting specific budget and conditions of execution in the place and / or workshop, transfers, insurance, etc., is necessary a contract of legal clauses, descriptive and technical reports, graphic documentation, status of measurements and budgets, which sometimes must be very detailed.

– Project management

- Preliminary draft

- Project

- Descriptive memory

- Technical memory

- Floor plans, heights and sections. Detail maps

- Specifying technical conditions

- Measurement status

- Budget

- Promotion

- Contract (terms of completion and billing)

- Billing. Management and taxes

– Reading plans

The scale

- The plant and top floor plan

- Heights

- The sections

- Perspectives and renders

- Demolition and new construction

- Models

Sound Installations – Marti Ruiz / Ivonne Villamil / Josep Manuel Berenguer

The course is divided into two parallel sections: one reflective/theoretical and the other practical. It concludes with the creation, production, and exhibition of a collaborative sound installation project with the participation of the students in the class.

Sound installation emerges at the intersection of many practices that have led to radical ideas about new forms of artistic creation. The term sound installation was coined by Max Neuhaus in the late 1960s and refers to a permanent or semi-permanent artistic form that exists both in public spaces and cultural contexts. These installations use sound to shape, transform, create, and define a specific space, and they do not exist in isolation but within their context: the context of their sound environment, their visual environment, and their social environment (Neuhaus 1994).

Throughout the course, the links between these interdisciplinary relationships are explored, observing how the spatial and relational qualities of sound are fundamental to building immersive environments. Through a collective research process, the aim is to foster critical thinking and provide a conceptual foundation for the creation of a final collective practical project. During the course, non-chronological analyses of seminal sound installations and relevant theoretical reflections are developed.

- Sound Installation – Theoretical Approaches· The course addresses ideas generated by theorists and creators who have reflected on the role of sound in space, and specifically on sound installations, including Max Neuhaus, Salomé Voegelin, Seth Kim-Cohen, Lucy Lippard, Brandon LaBelle, Gascia Ouzounian, Raquel Castro, and Christoph Cox, among others.

- Sound Installation – Context, Space, and Sound. In sound installation, context and space are essential elements that determine the relationship between sound and its environment. Context, understood as the physical, social, and cultural environment, influences how sound is perceived and experienced. Space, both architectural and social, acts as a vessel that modulates sound, transforming the listener’s perception. Works by seminal and contemporary authors from different geographical regions will be reviewed, including Max Neuhaus, Christina Kubisch, Janet Cardiff, Tania Candiani, Maryanne Amacher, Susan Philips, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, and Rebecca Horn, among others.

- Sound Installation – Creation, Production, and Public Presentation. Students will work practically on a collective sound installation, applying the theoretical and practical concepts discussed throughout the course. This collective project will involve the exploration and experimentation of sound in a specific physical space, considering both the architectural characteristics and the social and cultural context of the place. The final collective work will not only be a technical exercise but also a reflection on the relationship between space and sound, aligning with contemporary sound installation practices.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amacher, M. (2020). Selected writings and interviews. Blank Forms Editions.

Blesser, B., & Salter, L. R. (2009). Spaces speak, are you listening?: Experiencing aural architecture. MIT Press.

Brown, D. (2019, March 8). “Afropunk interview: Kevin Beasley.” Afropunk. https://afropunk.com/2019/03/afropunk-interview-kevin-beasley/

Cox, C. (2018). Sonic flux: Sound, art, and metaphysics. The University of Chicago Press.

Cox, C. (2009). Installing duration: Time in the sound works of Max Neuhaus. Yale University Press.

Cox, C., & Warner, D. (Eds.). (2009). Audio culture: Readings in modern music. Continuum.

DeLanda, M. (2011). A thousand years of nonlinear history. https://barbaraheld.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/e2809ca-thousand-years-of-nonlinear-historye2809d-manuel-delanda.pdf

Flynt, H. (n.d.). “Concept art.” http://www.henryflynt.org/aesthetics/conart.html

Glover, R., et al. (2019). Being time: Case studies in musical temporality. Bloomsbury Academic.

Gottschalk, J. (2017). Experimental music since 1970. Bloomsbury Academic.

Higgins, D. (n.d.). “Synesthesia and intersenses: Intermedia.” http://www.ubu.com/papers/higgins_intermedia.html

Hu, F. (2015). “Towards a non-intentional space.” e-flux. http://www.e-flux.com/journal/towards-a-non-intentional-space/

Illes, C., & Zummer, T. (2001). Into the light: The projected image in American art 1964-1977. Whitney Museum of American Art.

Kim-Cohen, S. (2009). In the blink of an ear: Toward a non-cochlear sonic art. Continuum.

Kisselgoff, A. (1988, March 3). New York Times review of 1988 revival of “Rainforest”. https://www.nytimes.com/1988/03/03/arts/dance-merce-cunningham-s-rainforest.html

Kuball, M., & Lersch, G. H. (2019). Res.o.nant. Sternberg Press.

LaBelle, B. (2008). Background noise: Perspectives on sound art. Continuum Books.

Larson, K. (2012). Where the heart beats, John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the inner life of artists. The Penguin Press.

Lippard, L. R. (1998). The lure of the local: Senses of place in a multicentered society. New Press.

Lucier, A. (n.d.). “Thoughts on installation.” http://kunstradio.at/ZEITGLEICH/CATALOG/ENGLISH/lucier-e.html

Lucier, A., & Simon, D. (2012). Chambers: Scores by Alvin Lucier. Wesleyan University Press.

MoMA Spaces – Pulsa: Jennifer Licht. (1969). Museum of Modern Art. https://archive.org/details/MOMASpaces

Mowitt, J. (2015). “Image.” In D. Novak & M. Sakakeeny (Eds.), Keywords in sound (pp. 176-189). Duke University Press.

Neuhaus, M. (1994). “Lecture at Siebu Museum Tokyo, 1982.” In Max Neuhaus: Sound works, Volume I, Inscription. Cantz.

Ouzounian, G. (2013). “Sound installation art: From spatial poetics to politics, aesthetics to ethics.” In G. Born (Ed.), Music, sound and space: Transformations of public and private experience (pp. 73-89). Cambridge University Press.

Reid, T. (n.d.). “Hearing the trauma you can’t see.” The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/hearing-the-trauma-you-cant-see/

Rogalsky, M. R. (2006). Idea and community: The growth of David Tudor’s Rainforest, 1965-2006. (Doctoral dissertation, City University London). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/42628585.pdf

Rogers, H. (2013). Sounding the gallery: Video and the rise of art-music. Oxford University Press.

Stirling, Ch. (2016). “Sound Art / Street Life: Tracing the social and political effects of sound installations in London.” Journal of Sonic Studies. https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/234018/234019

“The Experiential Turn — On Performativity — Walker Art Center.” (n.d.). Walker Art Center. https://walkerart.org/collections/publications/performativity/experiential-turn

Voegelin, S. (2010). Listening to noise and silence: Toward a philosophy of sound art. Continuum.

Wang, J. (2015). “Considering the Politics of Sound Art in China in the 21st Century.” In Leonardo Music Journal. Volume 25. The MIT Press.

Young, L. M., & Mac Low, J. (Eds.). (1963). An anthology of chance operations.