By Neemias Santos da Rosa, Postdoctoral Researcher.

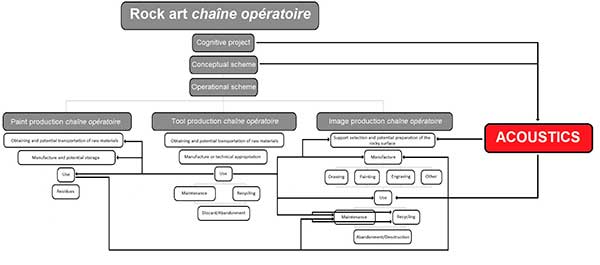

How does acoustics fit into the process of rock art production? Before answering this question, we need to clarify a fundamental matter: what is rock art made of? In her studies on rock art as a product of ideological and economic processes, archaeologist Danae Fiore considers that prehistoric visual representations comprise three essential parts: plastic composition, content and work process. The plastic composition corresponds to the visual image. It is directly linked to the content, which can be explicit or implicit and coincides with the cultural values of the human group that produces art. The connection between plastic composition and content takes place through the work process, which involves the practical combination of the elements that allow the production of the paintings or engravings (e.g. specific knowledge, raw materials, techniques, tools, pigments, supports, etc.). This production process occurs through the development of a chaîne opératoire (operational chain), a concept introduced by the French archaeologist and ethnologist André Leroi-Gourhan, in his book Le geste et la parole published in 1964. The chaîne opératoire is defined by this author as an ordered sequence of operations through which raw materials are obtained and transformed to manufacture a final product according to a previously determined model.

In recent years, archaeologists Marie Soressi and Jean-Michel Geneste have analyzed the history and efficacy of the chaîne opératoire approach in the study of past societies. According to these authors, such operational chain is structured on a cognitive project, which is translated into a conceptual scheme later materialized by a series of actions corresponding to an operational scheme. In the field of rock art, the cognitive project –also called the «graphic model» by the archaeologist Diego Gárate– corresponds to the mental designing of the final product, which is an idealized projection of the rock art image –with its specific cultural meanings– that the artist intends to create. Then, during the elaboration of the conceptual scheme, the rock art creator ponders various aspects of the productive process, such as what is the most suitable raw material to achieve the desired purpose, what are the resources available to satisfy the technical needs, and so on. At the same time, the artist verifies the availability of supports, reflects on the morphology of the image to be created, and think about the features of the tools necessary to accomplish the established objective.

After having structured the conceptual scheme, it is possible to carry out the operational scheme, which is developed according to a flow of actions based on the execution of the following steps, as suggested in my own PhD dissertation of 2019 and in several works published by Danae Fiore on the materiality of prehistoric art:

- Procurement and potential transportation of raw materials, with or without the use of tools from other production processes;

- Manufacture and/or technical appropriation of paint application tools and complementary tools, by using the raw materials obtained in step «a»;

- Manufacture and potential storage of paint, by using the raw materials obtained in step «a» and the tools resulting from step «b»;

- Selection of supports and potential preparation of the rocky surface, the latter through the use of tools from step «b»;

- Manufacture of images through drawing, painting, engraving or other technique, using the tools from step «b» and the paint elaborated in step «c»;

- Discard, maintenance or recycling of the tools;

- Use of the images;

- Potential maintenance or recycling of the images, through the use of the tools from step «b» and the paint resulting from step «c», or through the use of tools and paint coming from the development of another rock art production process;

- Abandonment or destruction of the images.

As can be seen in Figure 1, this proposed rock art chaîne opératoire can be subdivided into three parts that interact with each other to provide the manufacturing of tools, paint and images. Each part has its own steps and aims, but they are interconnected to achieve the final product. In this sense, it should be noted that the sequence of steps is not necessarily critical. Thus, for example, in the case of an unprepared support, the step «d» could even be the first of the entire sequence.

Figure 1. Acoustics in the rock art chaîne opératoire. Based on the model of rock art production sequence proposed by Dane Fiore in the article “The economic side of rock art: concepts on the production of visual images” published in 2007.

Then, we can go back to the first question: how does acoustics fit into the process of rock art production? Given that the perception of sound is an essential component of the human experience, we can say that acoustics of rock art places was probably sought during the production and use of rock art. In particular, on the basis of many works published by the members of the Artsoundscapes project (i.e. the book chapter by Díaz-Andreu and Mattioli in ‘The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art’, 2019), we can say that acoustics could have played an important role in step “d”, which is the selection of places to be decorated, and probably also in step “g”, which corresponds to the actions related to the use of the rock art images. Thus, choosing a shelter with special acoustic properties, instead of other available places without outstanding acoustic effects, the artist could reinforce the perceptual impact of the activities carried out in a site decorated with visual representations.

The identification of acoustics in the rock art chaîne opératoire can also provide information on other dimensions of prehistoric societies. Analyzing the relation between the abundance and scarcity of shelters with special acoustic properties in a given territory, as well as evaluating aspects such as the accessibility or inaccessibility to these shelters, it is possible to formulate hypotheses about the labor investment associated with the production of rock art. This investment increases the more time and energy is needed to carry out the different stages of the chaîne opératoire. Thus, a high labor investment can be seen as an indicator that other spheres of society related to the rock art representations, such as religion, would also be relevant enough to justify such investment. Therefore, acoustics can be seen as a key element not only in the formation of the rock art soundscapes, but in the production process that leads to the materialization and use of these symbolic images as well.