By Diego Moreno Iglesias and Antonio Torres Riesgo

Last January, the youngest members of the Artsoundscapes project travelled to southern Spain to examine first-hand the possibilities of archaeoacoustics in caves containing Palaeolithic rock art. The academic background of those travelling are varied and exemplify the interdisciplinary nature of the project, with members coming from the fields of archaeology, acoustic engineering and psychology. The idea was that this diversity of backgrounds would allow the team to incorporate a wide range of perspectives in their exploration.

The Artsoundscapes project was conceived as a comparative study of the archaeoacoustics in open-air shelters with rock art from around the world. The accessibility of the chosen locations suddenly was hampered due to the outbreak of the pandemic. The difficulties of travelling outside Europe led us to think about the possibility of working in caves with Palaeolithic art, all in Spain and therefore accessible to team members. Following this shift of spaces and chronology, a preliminary visit to some caves in the south of the Iberian peninsula was required to adapt the objectives and methodology to the new environment. The site chosen for this first visit was the Cueva de Nerja in Málaga, but, Covid-19 hit again! Due to complications caused by the virus among the Nerja workers we had to change destination at the last moment. Thanks to the assistance of Pedro Cantalejo, director of the Ardales cave research project and coordinator of the natural and historical heritage of the Guadalteba region, we had the fantastic opportunity to access the Ardales, Victoria, and Higuerón caves in Málaga.

Figure 1: Photos of our visit to the caves of Ardales (top), Victoria (bottom left, from left: Raquel Aparicio, Pedro Cantalejo, Samantha López, Diego Moreno and Antonio Torres) and Higuerón (bottom right).

Our visit to these Palaeolithic caves allowed us to get to know some of the different possible scenarios. Despite they all contain Palaeolithic rock art, their morphological and geological characteristics are very different, and so are the modifications they had been subjected to to make them accessible for tourism. With this in mind, we were able to appreciate how the physical differences of the caves influence their acoustics, and reflect on how to measure and study them in relation to rock art.

Acoustic testing of caves means a modification of the research techniques and questions developed so far in the project that had developed a methodology to work in the open air. To start with, there is no longer natural light, and the landscape forms, as we know them in the open air, are substituted by silhouettes moulded by water and the passage of time. More importantly, the acoustics of enclosed spaces are usually more remarkable than those in open spaces. We also felt that the sights and sounds that impressed the team in our visit could have had the same effect on prehistoric people, creating a link between cave paintings, the geological formations and the senses.

The relationship between cave art, the environment in which it is located, and the surrounding acoustics has been the subject of previous research. In order to carry out an exhaustive analysis of this phenomenon, it is necessary to review the successes and failures of previous investigations.

Abbé Glory (1964, 1965) was one of the first to investigate the relationship between rock art and the acoustics of their locations. He focussed on natural formations that emit sound when struck, which are known as lithophones, as well as the presence of cracks and calcifications, which could indicate their use in prehistoric ritual practices.

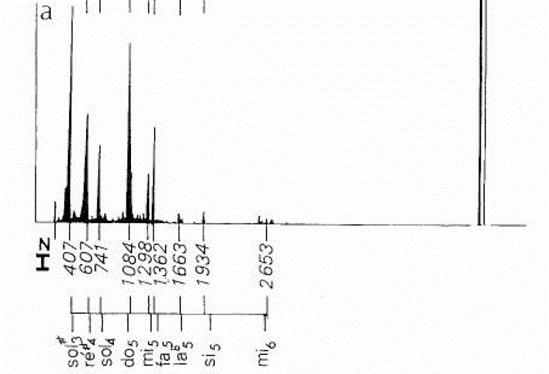

About two decades later Lya Dams (1984, 1985) carried out similar studies in these caves, expanding and confirming some of Glory’s hypotheses. She analysed the resonances that hitting some formations with stones and sticks elicitted and used musical notation to record their pitches. She also discussed possible combinations with other palaeolithic musical instruments and the potential audience.

Figure 2: Notes assigned to some of the lithophones in the cave of Nerja by Lya Dams

Although the works of Glory and Dams do not have the scientific rigour that further forays into the field would require – indeed, their methodology is unclear and it seems that no sound recordings were made – they laid the groundwork for later authors to carry out more complete studies.

Igor Reznikoff (1988, 2002, 2006) and Michel Dauvois (Dauvois & Boutillon 1990; Dauvois, 1994; Dauvois 1996; Dauvois, 2000) made key contributions to the field of archeoacoustics with their studies of Palaeolithic caves by attempting to map the association between acoustic phenomena such as resonance, sound amplification and reverberation with the location of pictorial motifs.

Reznikoff used his own voice to make sounds and documented the reverberations and resonances he perceived. Although his conclusions suggest that he found a correlation between certain motifs – points and marks – and acoustically singular zones, he later acknowledged that his method was imprecise and suggested the need for a more exhaustive analysis (Reznikoff, 2006).

Figure 3: Equipment inside of cave d’Arcy, where Reznikoff carried out acoustical exploration in 2019 (https://forum.ircam.fr/article/voices-from-resonant-spaces/)

French archaeologist Dauvois, working in the 90s with acoustician Xavier Boutillon, in contrast, employed more sophisticated methods, using precise acoustic sources and receivers. This technology is now outdated, but this would not be a problem if they had provided more e information about the measurement methodology employed. Questions remain regarding the location of the sound sources and the reasoning behind these. Many of the difficulties that they surely encountered during fieldwork when recording in uneven and humid caves, and the decisions made to overcome them, were left unrecorded and all those may have had an effect in the results obtained.

The aim of Dauvois and Boutillon’s reseach was twofold. On the one hand, they sought to investigate the relationship between the acoustics in areas with rock art in comparison with others without rock art. They concluded that their relationship was unsystematic. On the other hand, the authors carried out a record of the acoustic response of lithophones by recording the wide variety of sounds and frequencies that they can produce. This part of their study concluded that it is possible that they were used as a musical instrument in prehistory.

Figure 4: Michel Dauvois analysing a lithophone in Reseau Clastres (left) and representation of frequencies emitted by a lithophone (right)

Independently from the previous authors, in the early 1990s American archaeoacoustician Steve Waller also investigated the relationship between art and the presence of echoes and sound reflections, and, at the same time, he searched for information on the cultural understanding of sound in a series of ethnographic and historical sources. For his scientific experiments, his methodology consisted of using his own voice, clapping his hands, throwing stones and employing spring-loaded devices to create sounds that he would document via a hand-held recorder. He argued that there was relationship between the acoustical response obtained in a location and the content of rock art representations in them. In his studies of Palaeolithic caves he linked the depiction of ungulates and reverberation or, as he describes it, “strong sound reflections”. He also suggested that carnivores such as felines were represented in acoustically dull areas, reinforcing the idea that the placement of rock art was somewhat driven by acoustics (Waller, 1993). In his studies of the caves of Niaux and Cougnac he measured the strength of reflections in a manner similar to weather maps and once again reached similar conclusions (Waller, 2018).

Figure 5: Acoustical mapping of reflections measured by Steve Waller on Cougnac

In the 2010s a major technological leap was taken by the Songs of the Caves project (https://songsofthecaves.wordpress.com/). In this interdisciplinary project archaeologists (Pablo Arias, Roberto Ontañón, Manuel Rojo Guerra, Chris Scarre) worked together with experts in prehistoric instruments (Raquel Jiménez Pasalodos, Carlos García Benito and Simon Wyatt) and acousticians (Bruno Facenda and Rupert Till) (other members were Cristina Tejedor, Aaron Watson, Helen Drinkall and Frederick Foulds). The impulse response methodology was used and the results obtained were compared with the archaeological evidence in these places, especially as regards as the presence or not of particular rock art motifs. The impulse response methodology aims to record the acoustic response of a room to an impulsive type of stimulus, traditionally a balloon explosion, or gunshot (nowadays sinusoidal sweeps are usually employed). Acoustic parameters are extracted from this recording and, via an Ambisonics microphone, can be employed as a basis for auralisations, that is, simulations of how any acoustic source would sound in a given space.

The Songs of the Caves project worked in the caves of La Garma, El Castillo, La Pasiega, Las Chimeneas and Tito Bustillo (Till et al., 2013). The results of the project indicated that there was a weak statistical association between both low frequency resonances and moderate reverberation, and the positions of Palaeolithic painted dots and lines. The painted motifs were also collectively more statistically likely to be found in places with low reverberation and a high degree of intelligibility, clarity and definition (Fazenda et al. 2017). In addition to acoustics, other characteristics related to the location of the motives were significant, for example the distance from the cave’s entrance.

Figure 6: Rupert Till playing lithophones for Tito Bustillo (left) and some of the equipment used in the project Songs of the Caves (right)

Archaeoacoustics, especially in Palaeolithic sites, is now heading towards the use of 3D modelling, simulations, and virtual reality. The digital environment is able to merge geomorphological, acoustical and lighting data, and is a powerful tool for obtaining new archaeological information. The use of modelling allows for reconstruction of spaces which have unfortunately been permanently altered by nature or human hands, thus losing – or greatly modifying – their acoustical properties. An example of this cutting-edge technology and its uses is Armance Jouteau’s numerical simulation methods for both acoustics and illumination of the caves of Lascaux and Cussac in her doctoral thesis. Generally speaking, both models are based on the physical measuring of the acoustic properties of absorption and reflection of wall materials, and also the luminosity several sources of light such as torches or grease lamps (Jouteau, 2021).

Figure 7: Illumination (left) and acoustical (right) tests carried in situ by Armand Jouteau team

Bibliography

Dams, L. (1984): Preliminary findings at the ‘organ’ sanctuary in the cave of Nerja, Málaga, Spain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 3 (1): 1-14.

Dams, L. (1985): Palaeolithic lithophones: descriptions and comparisons. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 4 (1): 31-46.

Dauvois, M. (1994): Les témoins sonores paléolithiques. Extérieur et souterrain. ERAUL (Etudes et Recherches Achéologique de l’Université de Liège) [Otte, M. (ed.) Sons originels. Préhistoire de la musique, Actes du colloque international de Musicologie (Liège, 11-13 décembre 1993)]: 11-31.

Dauvois, M. (1996): Evidence of sound-making and the acoustic character of the decorated caves of the western Palaeolithic world. International Newsletter on Rock Art (INORA), 13: 23-25.

Dauvois, M. (2000): Des grottes et des sons. L’universe acoustique de Cro-Magnon. In Coget, J. (ed.). L’homme, le minéral et la musique. Modal. 10-23. Parthenay (Deux-Sèvres).

Dauvois, M. and Boutillon, X. (1990): Etudes acoustiques au Réseau Clastres: salle des peintures et lithophones naturels. Préhistoire, art et sociétés. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique de l’Ariège-Pyrénées, 45: 175-186.

Fazenda, B., Scarre, C., Till, R., Jiménez Pasalodos, R., Rojo Guerra, M., Tejedor, C., Ontañon Peredo, R., Watson, A., Wyatt, S., García Benito, C., Drinkall, H. and Foulds, F. (2017): Cave acoustics in prehistory: Exploring the association of Palaeolithic visual motifs and acoustic response. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 142: 1332-1349.

Glory, A. (1964): La Grotte du Roucadour (Lot). Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française. Comptes rendus des séances mensuelles, 61 (7 (présentations et communications)): CLXVI-CLXIX.

Glory, A. (1965): Nouvelles découvertes de dessins rupestres sur le causse de Gramat. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 62 (3): 528-536.

Glory, A., Vaultier, M. and Farinha Dos Santos, M. (1965): La grotte ornée d’Escoural (Portugal). Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 62 (H-S): 110-117.

Jouteau, A. (2021): Grottes ornées paléolithiques : espaces naturels, espaces culturels, art et déter- minisme. L’apport des modélisations, l’exemple de Lascaux et de Cussac. Archéologie et Préhistoire. Université de Bordeaux. PhD thesis.

Reznikoff, I. and Dauvois, M. (1988): La dimension sonore des grottes ornées. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 85: 238-46.

Reznikoff, I. (2002): Prehistoric Paintings, Sound and Rocks. In Hickmann, E., Kilmen, A. D. and Eichman, R. (eds.): Studien zur Musikarchäologie III: Papers from the 2nd International Symposium on Music Archaeology, Monastery Michaelstein (Germany), 2000. Rahden Orient-Archäologie 107. 39-56. Berlin.

Reznikoff, I. (2006): The evidence of the use of sound resonance from Palaeolithic to Medieval times. In Scarre, C. and Lawson, G. (eds.): Archaeoacoustics. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge McDonald Institute Monographs. 77-84. Cambridge.

Till, R., Wyatt, S., Fazenda, B., Sheaffer, J. and Scarre, C. (2013): Songs of the Caves: Sound and Prehistoric Art in Caves. Initial report on a study in the Cave of Tito Bustillo, Asturias, Spain. songsofthecaves.wordpress.com/ [Accessed: February 2022].

Waller, S. J. (1993): Sound reflection as an explanation for the context and content of rock art. Rock Art Research 10, 91–101.

Waller, S. J. (2018): Hear Here: Prehistoric Artists Preferentially Selected Reverberant Spaces and Choice of Subject Matter Underscores Ritualistic Use of Sound. In Büster, L., Warmenbol, E. and Mlekuž, D. (eds.): Between Worlds. Understanding Ritual Cave Use in Later Prehistory. Springer. New York.