Liquid crystals in different topologies and geometries

Javier Rojo-González, Alexis de la Cotte

Liquid crystals are partially ordered materials that constitute a phase of matter between solids and liquids. They present long range orientational order and some broken

translational symmetries which allows them to flow in at least 1D. One of the most paradigmatic cases are nematic liquid crystals, which are made of anisotropic building

blocks that tend to align in the same direction while preserving all of its translational symmetries allowing it to flow like a simple liquid. Moreover, nematic liquid

crystals can be described in the continuum approach by an apolar vector (director) field and an order parameter measuring how well the building blocks align in average at

each point.

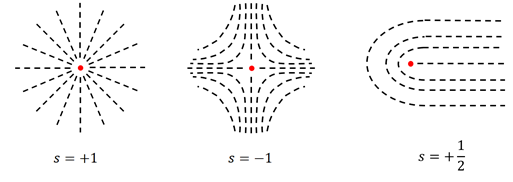

Since they can be described by an apolar vector field, they can present topological defects, which are singularities in the director field that can not be removed by a

continuous deformation of the director and are characterized by their topological charge (figure 1). These topological defects are able to preserve their own existence and

interact between each other through the elasticity of the medium, having attractive or repulsive interactions.

Figure 1: Examples of topological defects in 2D. Each topological defect is characterized by the topological charge which corresponds to the winding number. If two defects have the same topological charge they can be transformed continuously into each other, while if they have a different topological charge they can not be continuously deformed into each other.

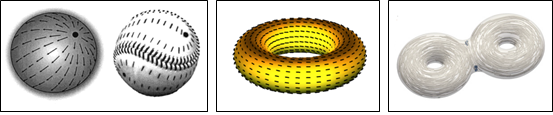

When confining a nematic liquid crystal into different geometries and topologies, the imposed boundary conditions can prevent the liquid crystal from achieving the locally preferred configuration everywhere leading to a frustrated configuration. This is specially exemplified by the Poincaré-Hopf index theorem, which states that if we have a director field tangent to a compact boundaryless surface, then the total topological charge (index, χ) of the confined director field is related to the number of handles of the surface (genus, g) by χ=2(1-g). This means that a director field confined to the surface of a sphere not only can not achieve the uniform parallel configuration it would prefer but that it also needs to have topological defects to fulfil the total topological charge of +2 imposed by the Poincaré-Hopf index theorem. Moreover, in the case of a torus there is no need for topological defects to appear since the total topological charge must be zero, while for a double torus the total topological charge must be -2 (figure 2).

Figure 2: Examples of a director field in the surface of a sphere (right), torus (middle) and double torus (right). For the sphere a configuration with two +1 defects and another with four +1/2 defects (both with total topological charge of +2) is shown. For the torus and double torus, a defect free configuration and a configuration with two -1 defects is shown respectively.

While the Poincaré-Hopf index theorem is a mathematical constrain, it is the physics of the system the one that determines the exact configuration that the system acquires

through minimization of the free energy.

The main objective of this project is to study equilibrium and dynamic aspects of topological defects in different geometries and topologies, more specifically,

how topology and geometry dictates the organization of ordered materials and how the curvature affects the dynamics of topological defects, which can be seen as “charges”

in some cases.

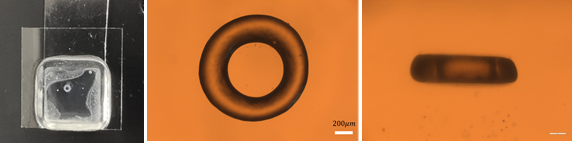

Figure 3: Nematic toroidal drop. Left: Nematic toroidal drop in sealed cuvette. Middle and right: Top and side view of the torus in the microscope.

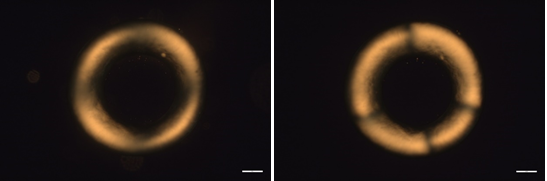

One of the systems of interest corresponds to a nematic liquid crystal (5CB) solid torus. The toroidal droplet is generated by the injection of the liquid crystal into a rotating cuvette filled with a yield stress material (figure 3). The yield stress material is able to stabilize the droplet due to its solid behaviour below the yield stress. Previous work in the group showed that instead of relaxing to the defect-free axially dull configuration, the nematic torus relaxed into a defect-free double twisted structure due the saddle-splay elastic term [1]. More interestingly, if one heats the liquid crystal to its isotropic phase and let it cool back into the nematic phase, it rarely relaxes back into a defect free configuration (figure 4 left), but relaxes to a configuration filled with stable defect structures (figure 4 right). Moreover, we always find the same two types of defect structures, defect pairs and “X” patterns. Exploring the role of the Gaussian curvature with slenderer tori and even cylinders, the same defect structures are found, which suggest that the Gaussian curvature is not responsible for their appearance and stabilization.

Figure 4: Cross-polarizer images of 5CB torus. Left: Defect free configuration after made. Right: Defect populated configuration after heating and cooling back.

This toroidal droplets can also be made with other types of liquid crystals, like cholesteric or chromonic liquid crystals. While the cholesteric liquid crystal presents a

higher frustation when confined leading to a very rich and complex variety of director configurations, chromonic liquid crystals present a very low twist elastic constant,

favouring double twist configurations.

Another interesting system we aim to study experimentally is that of a nematic liquid crystal confined to the surface of a cone (2D nematic). The case of the cone is

geometrically very interesting since it presents zero Gaussian curvature everywhere except at the tip where it has a finite Gaussian curvature accumulated there. This

means that a being living on the surface of a cone is not able to tell the difference between the cone and a plane except at the tip. Recent theoretical studies have

shown that under the right boundary conditions and for certain cone angles, a +1/2 defect is expelled from the tip to the body of the cone [2]. It would be interesting

to test experimentally the theoretical claim.

[1] E. Pairam et al, PNAS 2013, 110, 23, 9295–9300.

[2] F. Vafa et al, Physical Review E 2022, 106, 024704.